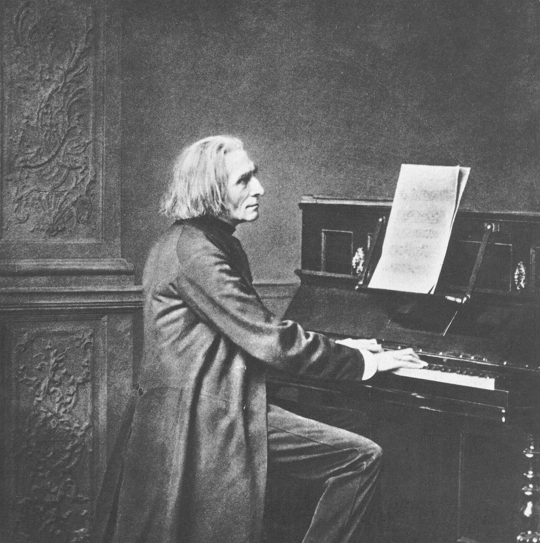

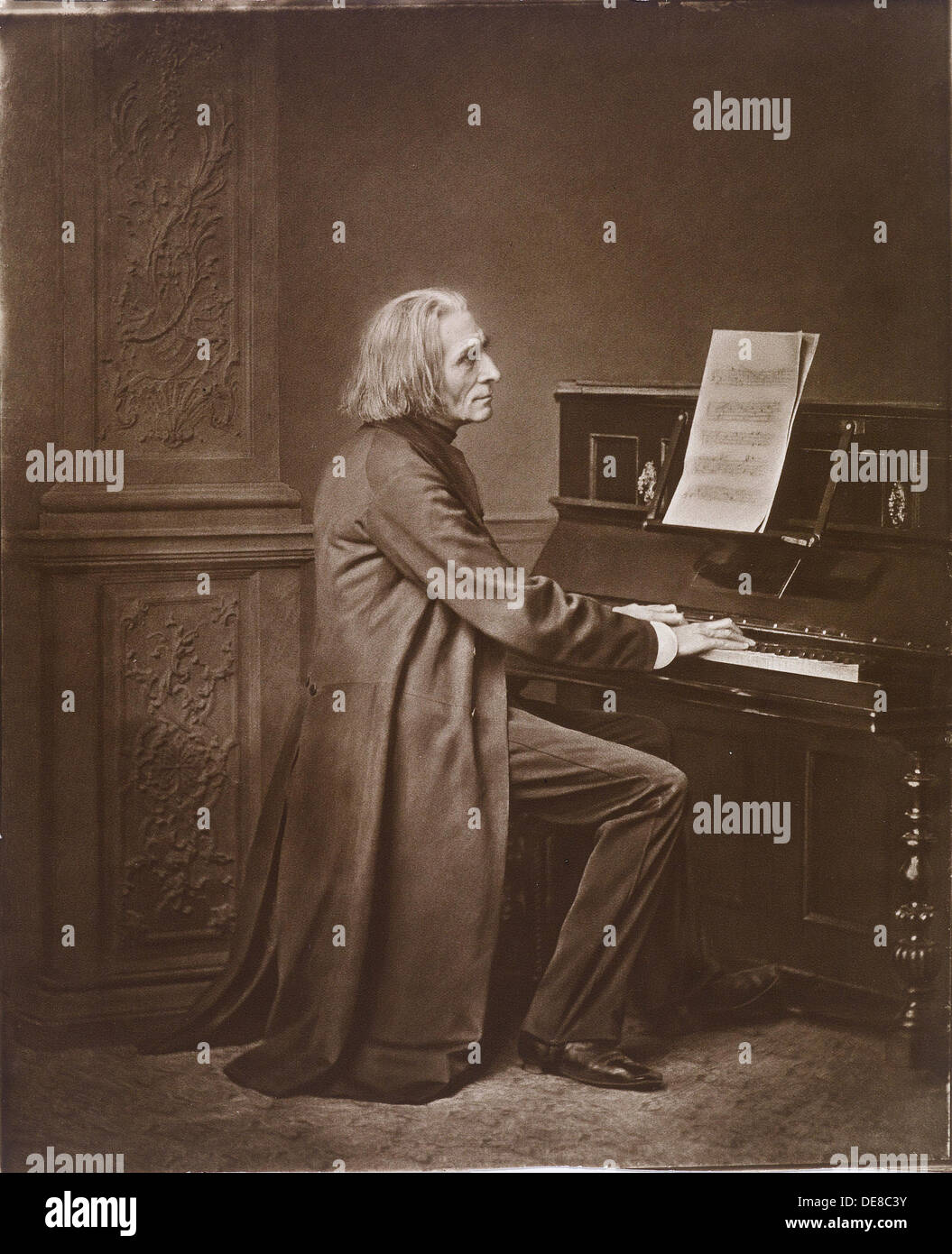

The same can said for his transcriptions of works by Bach and Beethoven, where music written for one medium is translated into another. His elaborations and fantasies for the piano based on the operatic works of others suggest many ways of freely adapting and altering music we like and wish to remember. Notation in his piano music sought to mirror an art that was spontaneous and tied to a moment of performance. Few, if any classical musicians can do it. At the heart of his music for the piano was improvisation, an art sadly lost in what we now term classical music. The last effort in a major city to revive Liszt’s music took place in New York in the 1970s under the leadership of Pierre Boulez. If one compares this to Liszt’s output, not only for the piano, (which is gargantuan in scope), one cannot help but be struck by the obscurity that most of his music has fallen into. The choral and organ music are never performed. This is in stark contrast to Chopin, his contemporary, whom Liszt championed. Pianists bring out a few select works in recital, mostly to display the virtuosity they demand. Only a few of his works are still in the standard orchestral repertory - the piano concertos and one tone poem Les Preludes. Yet our attention to him remains largely muted and ambivalent. Celebrating the 200th anniversary of his birth ought to have been an opportunity to revisit a figure who helped define Romanticism, the role of the piano on the stage and in the home, and, most importantly, how music functions for most of the literate public. The case of Franz Liszt, who was born in 1811 and died in 1886, is more complex.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)